Radioactive Legacy

The Human Cost of America’s Secret Radiation Experiments

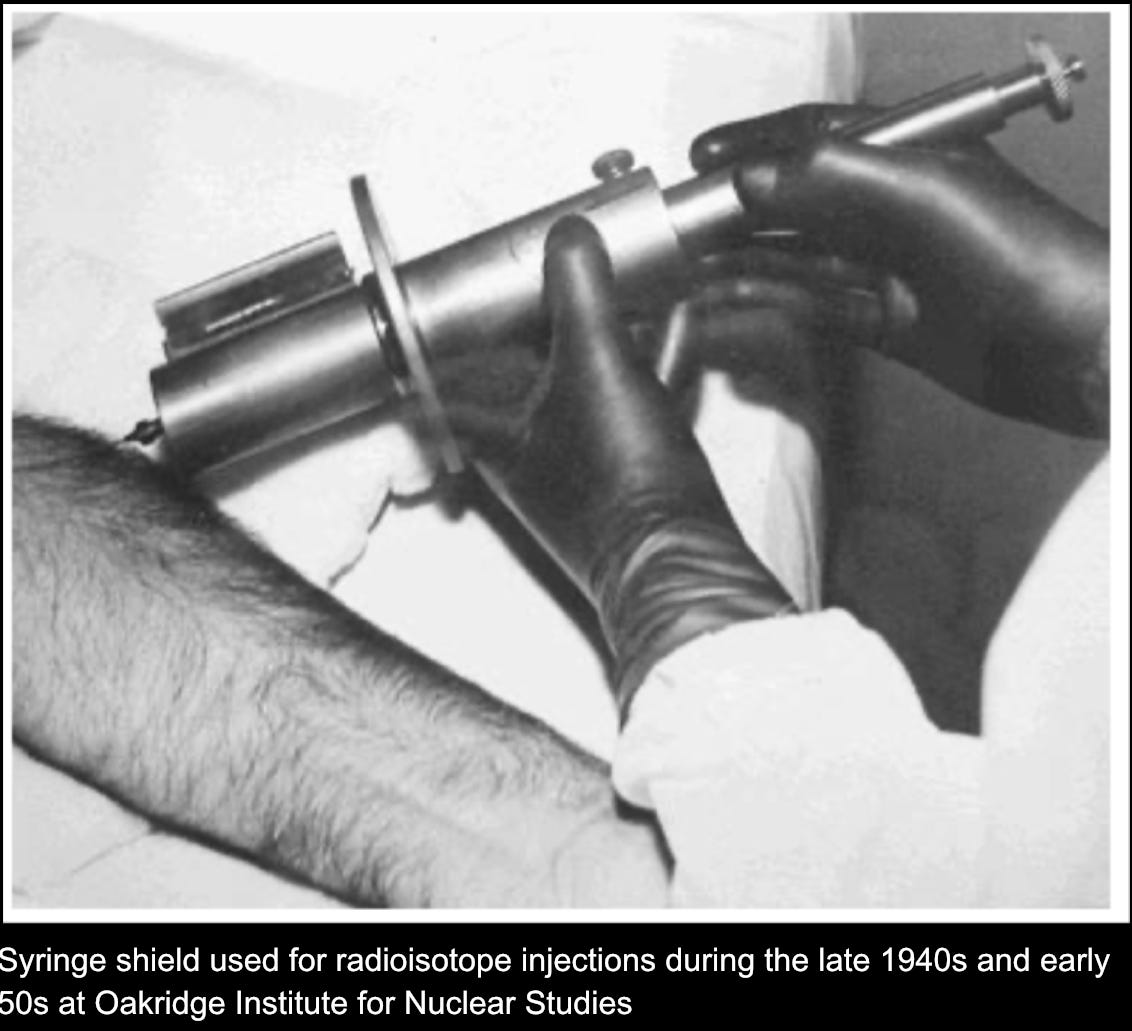

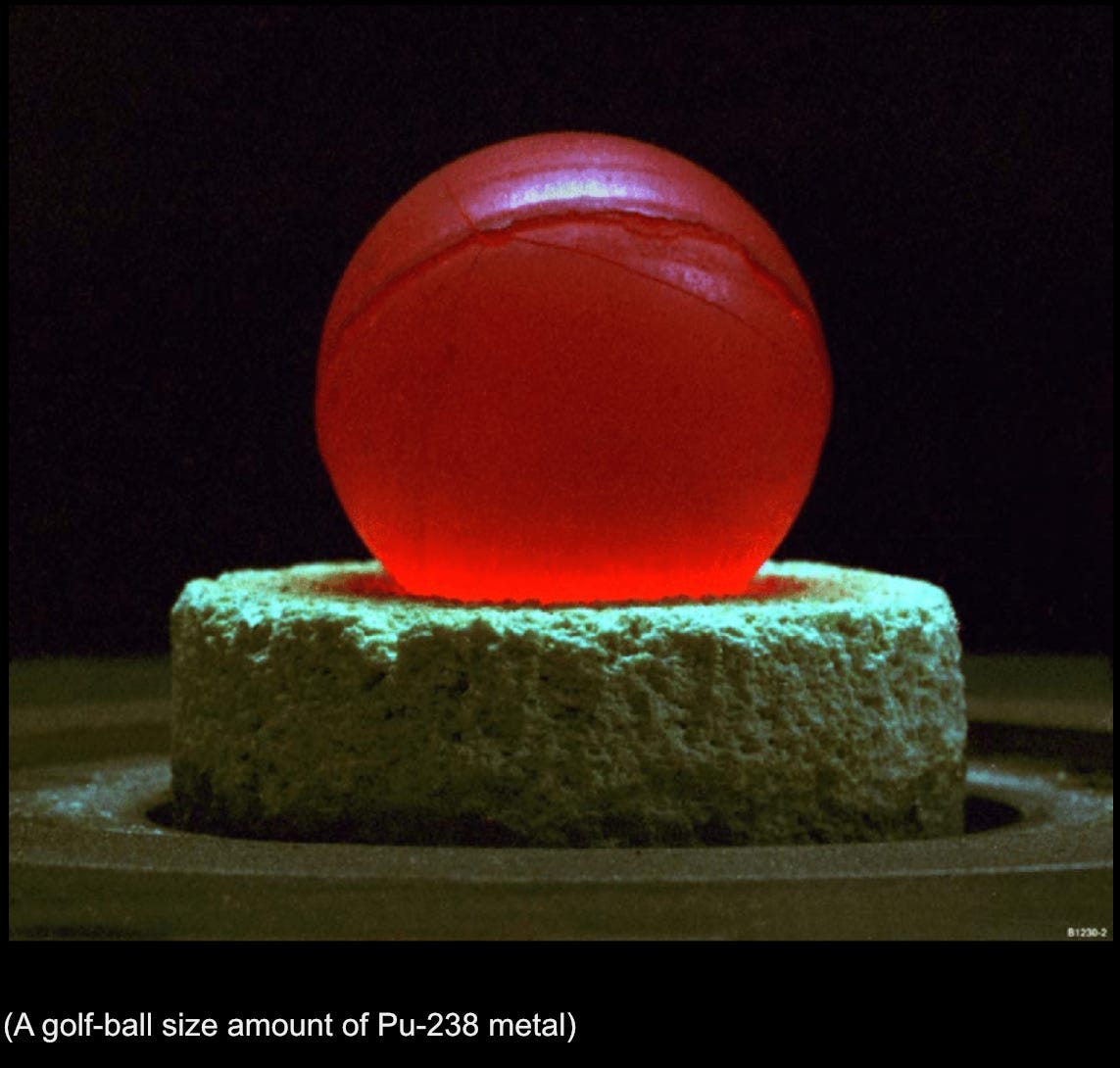

Deep in the atomic fever of the 1940s, a handful of American hospitals became unwitting crime scenes. In one case, a 36-year-old African-American railroad porter named Elmer Allen lay on the gurney at a San Francisco hospital in July 1947, believing doctors were treating his bone cancer. In truth, government physicians were about to inject his leg with plutonium, a radioactive metal so intense it glows with its own heat. Allen’s left leg was amputated shortly after, ostensibly to remove the tumor – but also to harvest bone riddled with the plutonium they’d put there. He was one of 18 human subjects covertly injected with plutonium under the Manhattan Project and early Cold War programs. Each was a “CAL” or “CHI” code in some secret ledger; each was a living experiment in how long an “expendable” human body might carry the atomic poison.

It started with Ebb Cade, a Black construction worker at Oak Ridge who had the misfortune of surviving a car wreck near the Manhattan Project site in 1945. With broken bones from the crash, Cade was brought to an Army hospital – where doctors saw not a patient, but an opportunity. They delayed setting his fractures for five days so they could inject him with 4.7 micrograms of plutonium and then extract samples of bone before properly treating him. They even pulled 15 of his teeth to test how plutonium spread in his body . Cade was never told why his treatment was so strangely cruel; he apparently suspected something and fled the hospital in the night before they could do more. He died in 1953 of heart failure, never knowing he’d been the first human plutonium test subject.

After Cade, the experiments moved to Chicago and San Francisco. In Chicago, three cancer patients (coded CHI-1, CHI-2, CHI-3) were dosed with plutonium in 1945–46 . The doctors chose people who were already dying – or so they thought – to avoid “wasting” a healthy body. As one report coldly noted, they selected patients whose life expectancy was so short “they could not be endangered” by the plutonium injection. In one instance, a man with mouth and lung cancer (CHI-1) got 6.5 micrograms and died within months. Another, a woman with metastatic breast cancer (CHI-2), was injected with a massive 95 micrograms, the highest plutonium dose given and died 17 days later. The third (CHI-3), a young man with Hodgkin’s disease, also got 95 micrograms and passed away sometime thereafter. The physicians recorded reams of data from these dying patients’ urine and blood, as if harvesting science from their last days on earth. There was no mention of consent in any of the Chicago records. Why bother asking a dying person to sign a form, when in the doctors’ eyes they were already as good as dead?

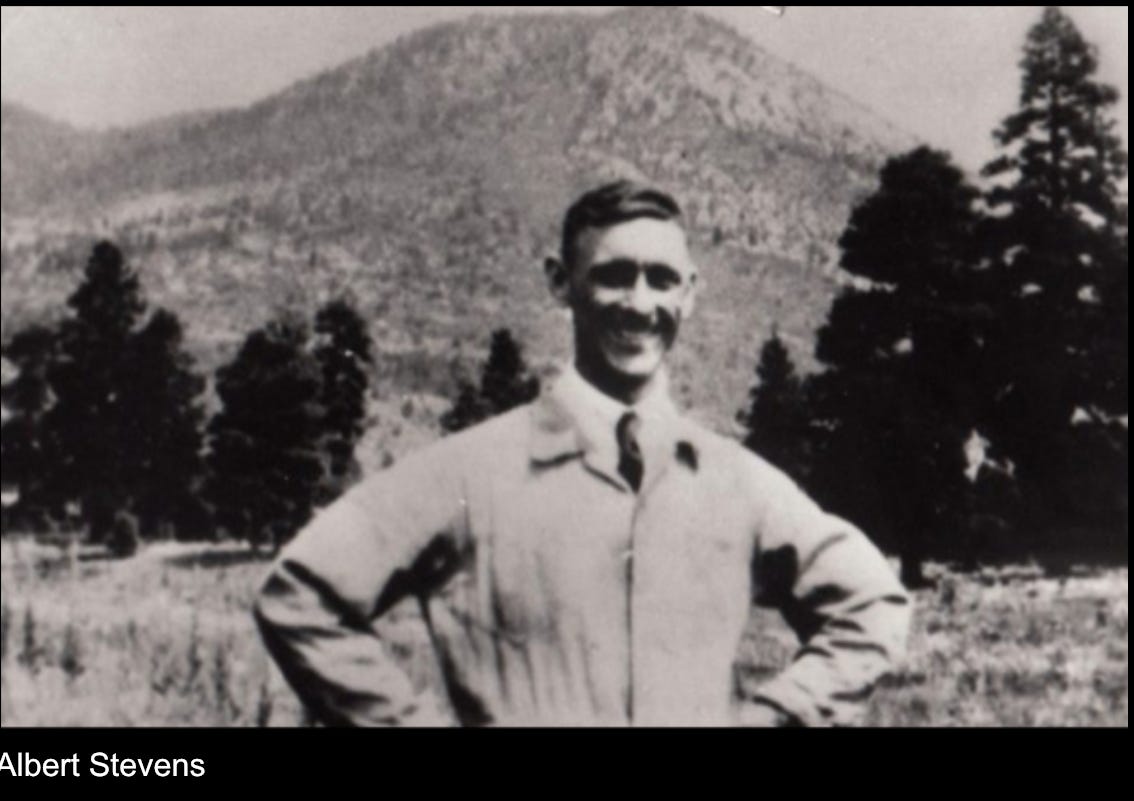

It was in California, however, that the plutonium program took an especially surreal turn. Dr. Joseph Hamilton at UCSF led the West Coast effort, hunting for “suitable patients” like a fisherman for experimental prey. Albert Stevens, a 58-year-old house painter misdiagnosed with terminal stomach cancer, became CAL-1 in May 1945. Doctors injected him with plutonium in his stomach lining and only afterward discovered Stevens didn’t even have cancer, just a benign ulcer . But rather than celebrate, the team saw a golden chance: here was a healthy man walking around with plutonium in his body. They collected his urine and feces daily for almost a year, measuring the radioactive excreta with ghoulish glee. When Stevens thought of moving away, Hamilton schemed to pay him $50 a month to stay nearby – not out of compassion, but so the government wouldn’t lose its valuable human lab rat.

A secret memo even outlined options: perhaps put Mr. Stevens on a phony “payroll” job to justify the payments, and “not recommend” paying him “as an experimental subject only” (too obvious!). They ultimately did pay him a stipend, and of course never told him why. In fact, one Berkeley researcher later admitted that Stevens went to his grave never knowing what had been done: “to my knowledge he never found out,” the scientist recalled, adding that Stevens’s sister, a nurse, “was very suspicious” but never got answers. During the surgery to treat his ulcer, the doctors seized their moment and sliced out samples of Stevens’s spleen and a rib, healthy tissue cut from his body purely to see how much plutonium had lodged in it. The pathology lab never saw those specimens; they went straight to Hamilton’s secret project. Albert Stevens miraculously survived for 21 more years, carrying the highest known internal radiation dose of any human. He died of heart failure in 1966, never told that the “therapy” he received was in fact an atomic trial.

Stevens’s case set the template: don’t ask, don’t tell, and don’t waste a good corpse. The experiments continued under new codenames. In April 1946, CAL-2 was selected: a 4-year-old boy from Australia named Simeon Shaw, flown to UCSF with osteosarcoma (bone cancer) in his arm . His parents sought hope; what they got was betrayal. Within days of arriving, little Simeon was injected with a cocktail of plutonium along with tracer doses of yttrium and cerium. The doctors told the Shaws this was part of a cutting-edge treatment, even removing part of the boy’s tumor a week later and sending it to the lab to see how much radioactive material had penetrated it. In truth, the injection was never intended to cure him. It was a data grab, pure and simple, an experiment piggybacking on the child’s tragic illness. Simeon was sent home with no follow-up; he died in January 1947, his grieving parents none the wiser. They would not learn for thirty years that their dying child had been used as a human beaker of plutonium.

By late 1946, even the military brass got cold feet. Manhattan Project chief Colonel Kenneth Nichols ordered a temporary halt to these human injections at UC Berkeley, vaguely claiming such work was “not authorized” under the bomb program. But the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) took over in 1947 and quietly resumed some experiments under tighter secrecy. One AEC edict dubbed the “Wilson memo”, nominally required that human experiments have a therapeutic intent and some form of consent. In practice this translated into a wink-nod, half-truth approach. At Berkeley, Hamilton and colleagues allegedly told patients only that they would get an injection of a “new substance… too new to say what it might do” but with similarities to treatments that “control growth processes”, a vague bait-and-switch implying a possible cancer therapy. As the AEC’s first biomedical chief later admitted, “you could not call it informed consent”, since patients were misled to think it might help them. In June 1947, with these perfunctory rules in place, the California team went right back to work.

They found CAL-A, a teenage boy at a San Francisco hospital, and injected him with americium, another radio-element, using “the same procedure as with Mr. S” (Albert Stevens) . The boy was Asian-American and only “informed” through a guardian, if at all, no records of real consent remain . Then came CAL-3: Elmer Allen, the man with the glowing leg. Allen was a working father of two with chondrosarcoma, a slow-growing bone tumor in his knee. In July 1947, doctors injected plutonium directly into his tumor and amputated his leg days later, claiming it was necessary for his cancer.

In reality, they had what they wanted, his plutonium-soaked bone in a jar, ready for analysis. On the chart, two doctors noted that the “experimental nature” had been explained and that Allen “agreed to the procedure”, being of sound mind. This CYA note was likely written to satisfy the new AEC rules, but it’s doubtful they told Mr. Allen the full story, that the injection was solely to gather data, not to help him. In fact, internal memos show the experiment violated the Wilson memo’s key requirement of a therapeutic expectation. They knew it would do nothing for him. Tragically, Allen’s cancer was actually treatable; once his tumor was removed (by amputation), his prognosis was “moderately good” and he could have lived many years, which he did, surviving until 1991. But those years were shadowed by mystery and injustice. Decades later, Elmer Allen’s daughter recalled how her father remained deeply troubled. At a 1995 government hearing, she testified: “We contend that my father was not an informed participant in the plutonium experiment… He was asked to sign his name several times… Why was he not asked to sign his name permitting scientists to inject him with plutonium? Why was his wife… not consulted?” The family only learned the truth in the 1990s, and by then Elmer Allen was long gone – labeled paranoid in life for suspecting a government plot, vindicated only after death.

“Whole Body” Radiation: The Cincinnati Trials

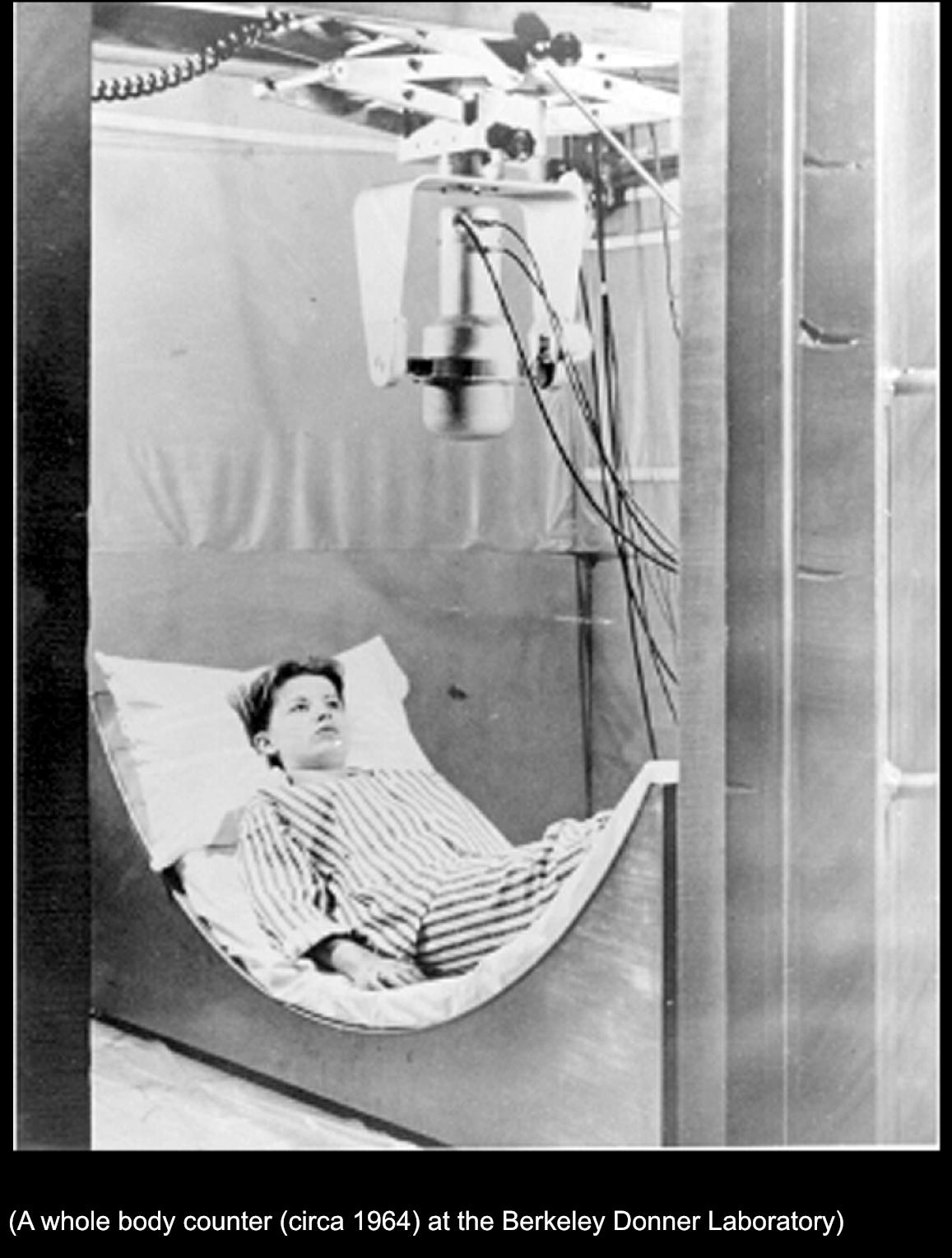

The human radiation saga did not end with the plutonium files of the 1940s. In the 1960s, as the Cold War flared, a new chapter of abuse unfolded in hospital radiation wards. At the University of Cincinnati, radiologist Dr. Eugene Saenger embarked on a Department of Defense-funded project that would expose at least 88 unwitting patients to massive total-body irradiation (TBI) between 1960 and 1971. These patients, mostly poor men and women with advanced cancer, believed they were receiving experimental treatment for their illnesses. In reality, many were being bombarded with radiation to simulate nuclear battlefield conditions for military research. The Pentagon wanted to know: how much radiation can a soldier survive? Saenger’s human subjects became stand-ins for soldiers, guinea pigs in hospital gowns.

Saenger’s team drew from Cincinnati General Hospital, a public hospital serving the city’s low-income and Black residents. Many were charity cases with cancers deemed incurable. They were not told that the U.S. military was bankrolling the experiment, nor that the radiation dosages had nothing to do with curing them. In fact, for the first five years of the study, no consent forms at all were used. Later, minimal consent was obtained, but patients still weren’t warned that the full-body radiation could induce intense suffering or even hasten death.

Under this barbaric protocol, patients were placed in specially designed radiation suites and exposed to whole-body X-ray doses up to 200 rads in a single sweep. (For comparison, 400–500 rads delivered acutely can be lethal; even 100–200 rads cause severe radiation sickness.) Saenger later defended that the maximum dose, 200 rads, was “only” a fifth of some modern therapeutic regimens. But context is everything: modern therapies might fractionate doses and aim at tumors, whereas Saenger’s subjects got a brutal one-time blast to the entire body, often with no genuine therapeutic aim. The results were predictable and ghastly. Patients vomited, suffered debilitating nausea, burns, confusion, and pain. Some died within days or weeks of the irradiation. An estimated 21 people died within a month of their exposure, far more than expected from their cancer alone. In one egregious instance, medical records show no evidence of pain relief given to a man who writhed in misery after his whole-body dose, the study protocol treated morphine as a data-contaminant.

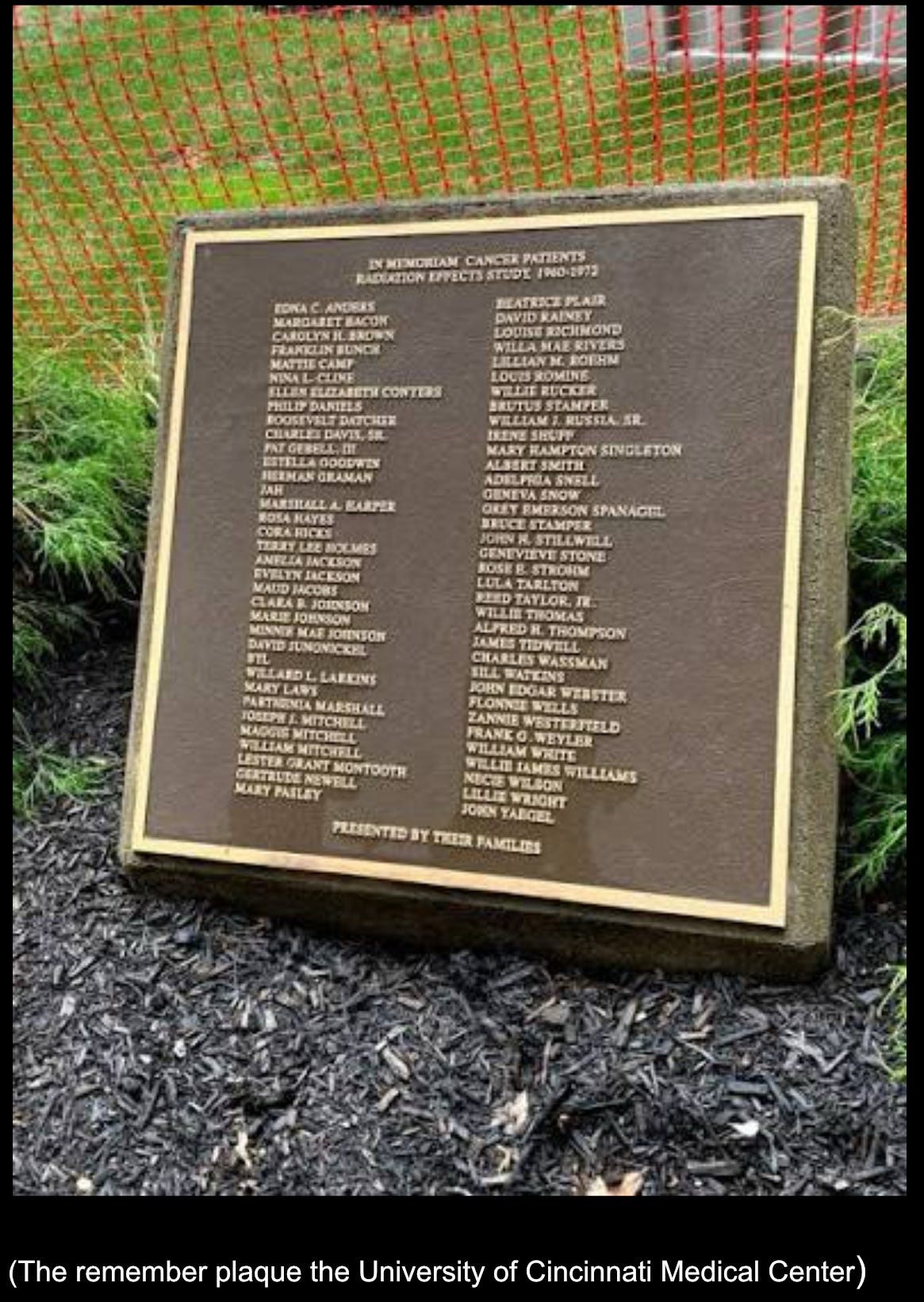

Saenger, of course, maintained to the end that he was trying to help his patients. “One purpose of the study was the relief of pain, shrinkage of cancer and improvement of well-being,” he told a 1994 congressional panel with a straight face. The second purpose, he admitted, was to “study the systemic effect of radiation”, i.e. to see what nuclear war might do to a person. His critics didn’t buy the altruism. They pointed out that many patients showed no cancer improvement from these blasts; if anything, evidence later suggested the heavy radiation shortened their lives. Families testified that their loved ones were treated like expendables because they were poor, uneducated, and Black. By the late 1960s, even the Pentagon grew wary of bad PR. Senator Edward Kennedy helped shut down the DOD contract in 1972 after media reports, and the experiments quietly halted. But the truth remained buried for two more decades. No one informed the victims or their families that the treatments had been a military experiment in disguise, not until the 90s, when declassified files and whistleblowers brought it all to light.

When the truth finally surfaced, it read like a horror script. In 1994, the families of Cincinnati victims filed a class-action lawsuit. In court, Judge Sandra Beckwith likened the experiments to Nazi doctors and explicitly invoked the Nuremberg Code, which the U.S. had ostensibly embraced after World War II. The university settled in 1999, paying out a few million dollars – a pittance for 88 stolen lives. A memorial plaque with 70 names (the known dead at the time) was dedicated in 2000 on the medical campus. But even that token of remembrance was botched: it omitted dozens of names (mostly Black patients who hadn’t had family in the lawsuit), and the plaque itself was soon tucked away behind a parking garage, literally allowed to become overgrown with weeds. Out of sight, out of mind, much like the entire episode of these Cold War radiation trials. As one survivor’s family member bitterly observed, the lackluster plaque is a “physical manifestation of this story’s fading place in history”. Indeed, had it not been for the dogged activism of locals and a brave whistleblower (Martha Stephens, a UC professor who exposed the experiments in 1972 ), the Cincinnati tests might have remained a dark, unspoken secret. Instead, they stand as a glaring reminder that, in the pursuit of “national security,” doctors in America crossed some of the very lines for which we hung Nazi physicians at Nuremberg.

Radioactive Tracers in Children’s Cereal

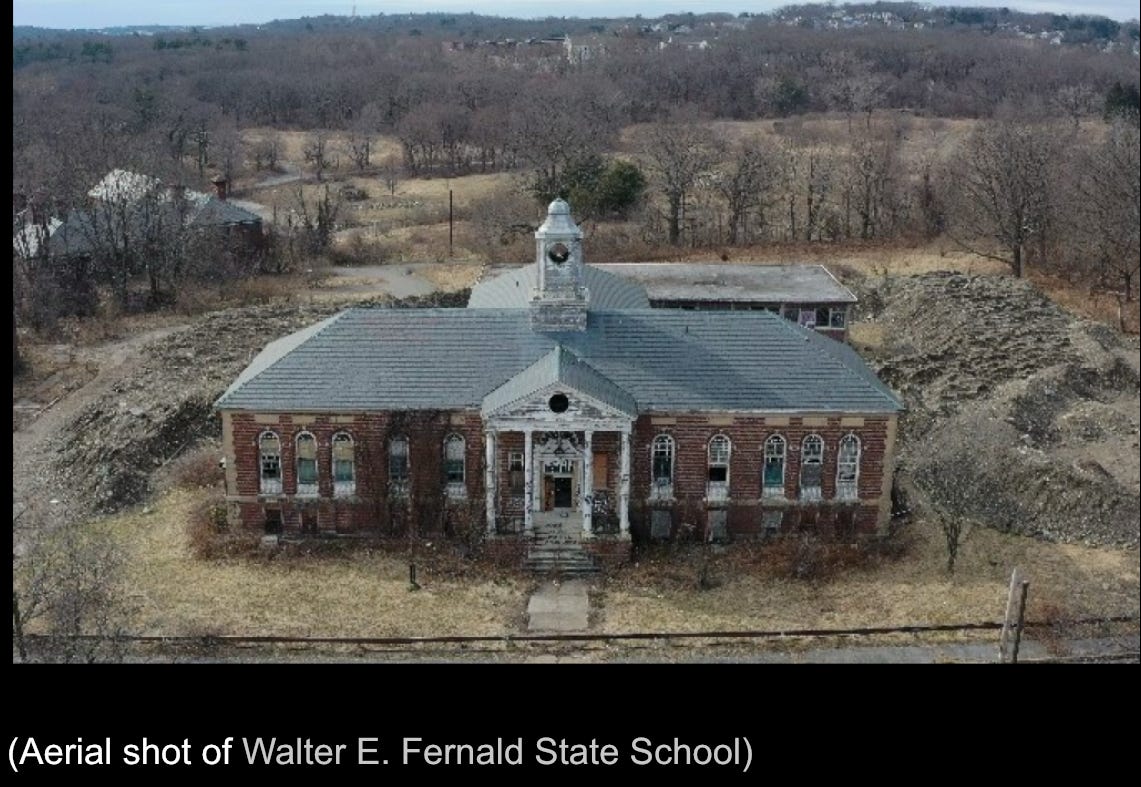

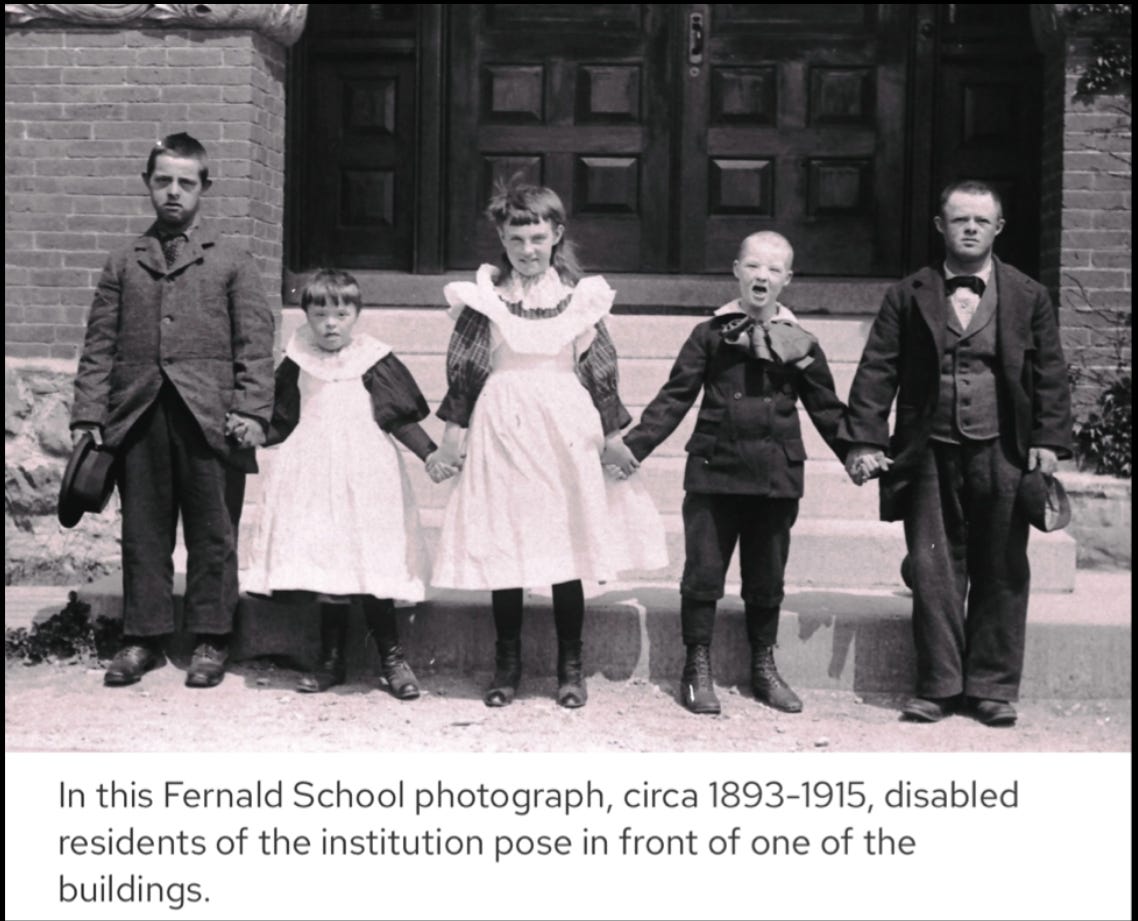

Perhaps the most perverse of all was the decision to carry out radiation experiments on children, many of them disabled or orphaned, under the guise of science and nutrition. In the late 1940s and 1950s, prestigious institutions like MIT and Harvard teamed up with industry (hello, Quaker Oats Company) to test nutritional theories using radioactive tracers. The stage for one such experiment was the Walter E. Fernald State School in Waltham, Massachusetts, a bleak institution for so-called “feeble-minded” children, some intellectually disabled and others simply wards of the state with nowhere else to go. Life at Fernald was already Dickensian: children were warehoused, abused, malnourished, and exploited for menial labor. But even these everyday cruelties were not enough for the men in white coats. In 1946, researchers recruited a group of boys into a special “Science Club.” The boys, ranging in age from about 10 to 17, were enticed with promises of extra milk and oatmeal at breakfast, trips to baseball games, and gifts like Mickey Mouse watches. For children who were normally treated as subhuman, the Science Club sounded like heaven, no more lumpy porridge in the communal hall, but a hearty breakfast with sugar and privilege. They had no idea the oatmeal was laced with radioactive iron and calcium.

Over several years, 74 Fernald boys were thus dosed with radioisotopes as part of nutrition studies . In some cases, they ate the fortified Quaker oatmeal; in others, researchers went so far as to inject radioactive calcium directly into the boys to see how it deposited in bones . The intent, at least on paper, was to answer questions about mineral absorption and phytates in cereal grains. But the methods were breathtakingly unethical. Neither the children nor their guardians (when any existed) gave informed consent, and in fact most were never even told they were part of an experiment . The Fernald superintendent had legal guardianship over many state wards and blithely signed off on the studies, essentially consenting on behalf of the boys to experiment on themselves, an outrageous conflict of interest later condemned by state investigators.

One member of a 1994 task force remarked that these experiments “violated the Nuremberg Code”, established just a few years earlier, by using kids who could not consent and giving them radioactive substances without their knowledge. The researchers defended themselves by saying the doses were small (indeed, they were low, the exposures were later found to be within safe limits ). But that’s beside the point. The boys at Fernald were treated like lab rats, not children. “We just thought we were special,” recalled Fred Boyce, a club member, decades later, finding out the truth “felt like a deep betrayal”.

It took until 1993 for the Fernald experiments to hit the news, sparked by reports of Cold War human experiments nationwide. The state of Massachusetts convened a task force and MIT, deeply implicated, scrambled into damage control. In an awkward public apology, MIT’s president acknowledged “the young people apparently were not informed” that the study involved radioactive tracers. The Institute insisted no harm was done, citing expert analyses that the children’s leukemia risk was not elevated, a cold comfort of statistics . Eventually, a class-action lawsuit was filed on behalf of the Fernald boys (by then grown men). In 1998, MIT and Quaker Oats settled, paying out $1.85 million – roughly $60,000 per survivor.

As part of the settlement, MIT still denied wrongdoing, calling the study an unfortunate product of its time but claiming its researchers “acted properly under then-existing standards” . Properly? One shudders to think what improper would have looked like. The boys who had been used finally got some compensation, but what they really wanted was an apology that fully acknowledged their stolen childhoods. Fred Boyce, who spent 11 years confined at Fernald for no sin but being unwanted, said the worst part wasn’t the radiation per se – it was being labeled a “moron” and treated as less than human. “They took away my childhood and my education,” another survivor, Joe Almeida, lamented. “The two things you need in life to make it, they took from me”. And for what? So Quaker Oats could edge out Cream of Wheat in the breakfast wars by proving their cereal had iron absorption just as good as the competitor’s? The banality of the motive, corporate marketing data, makes the cruelty all the more monstrous.

Fernald was not the only site of pediatric radiation research. Across the country, similar tracer studies were done on vulnerable groups. In Tennessee, pregnant women at a poor clinic were given “vitamin drinks” containing radioactive iron to study fetal absorption – without consent, of course. In New York and Illinois, researchers exposed developmentally disabled children to radioiodine to gauge thyroid function. The pattern was the same: they targeted the voiceless, kids, orphans, the disabled, the chronically ill, those least likely to understand or protest. One 1950s paper chillingly referred to institutionalized children as “experiments of nature” ready to be exploited. And exploit them they did.

Prisoners and the “Privilege” of Radiation

If children and the sick were fair game, why not prisoners? During the 1960s, the AEC (and later NIH and even NASA) sponsored a series of testicular irradiation experiments on inmates in Oregon and Washington state. The logic: astronauts and nuclear workers might face radiation that could affect fertility, so someone had to figure out the dose at which a man becomes sterile or sires deformed offspring. Who better than incarcerated men to serve as human test subjects? At least 130 prisoners were enrolled, lured by token payments and promises of parole considerations. The most infamous of these studies took place at the Oregon State Penitentiary from 1963 to 1973 under Dr. C. Alvin Paulsen (with parallel work by Dr. Carl Heller in Washington).

The procedures read like mad science. Prisoners, usually young, disproportionately people of color, were asked to lie down in a contraption akin to a coffin with only their testicles exposed in a small water bath. Then, without anesthesia, the researchers zapped their testicles with X-ray beams at varying doses. One inmate, Harold Bibeau, age 23, recalled being ushered in on September 29, 1965, made to place his groin under the machine and “lowered his testicles into water” before the radiation was applied. He didn’t know it at the time, but he received about 18 rads to his gonads in that session. Others got far more – some up to 600+ rads to the testicles delivered in multiple sessions, a dose that would be fatal if given to the whole body. The prisoners were typically given $5 per month for participating, plus small bonuses for enduring painful biopsies of their testes and ultimately a vasectomy (which the researchers strongly recommended to prevent any radiogenic mutations from fathering children). Indeed, many men agreed to surgical sterilization at the end in exchange for an extra $100 or so, essentially signing away their ability to have kids as the final payment for being a human lab rat.

Researchers assured the convicts that the risks were minimal and the value to science immense. In truth, they knew radiation could shatter chromosomes and cause cancer, sterility, and birth defects, that was the very point of the study. Follow-up was cursory at best. Years later, at least one participant developed testicular cancer; others suffered mysterious aches, rashes, and psychological trauma. “No one ever sat us down and explained… the complications,” former inmate Robert Garrison said. “Worst of all is the deceit… I can’t even get a doctor to acknowledge my problems” might be related, he complained . Another, Phillip King, said he lives with constant groin pain and anger: “I took part in the tests and now I’m in a lot of pain… I think I’m owed something”. The psychological toll was real: prison officials noted some men experienced sexual identity crises and depression after having their testicles irradiated and disfigured by biopsies. Who would have thought? Treat people like lab animals and they might suffer emotionally as well as physically.

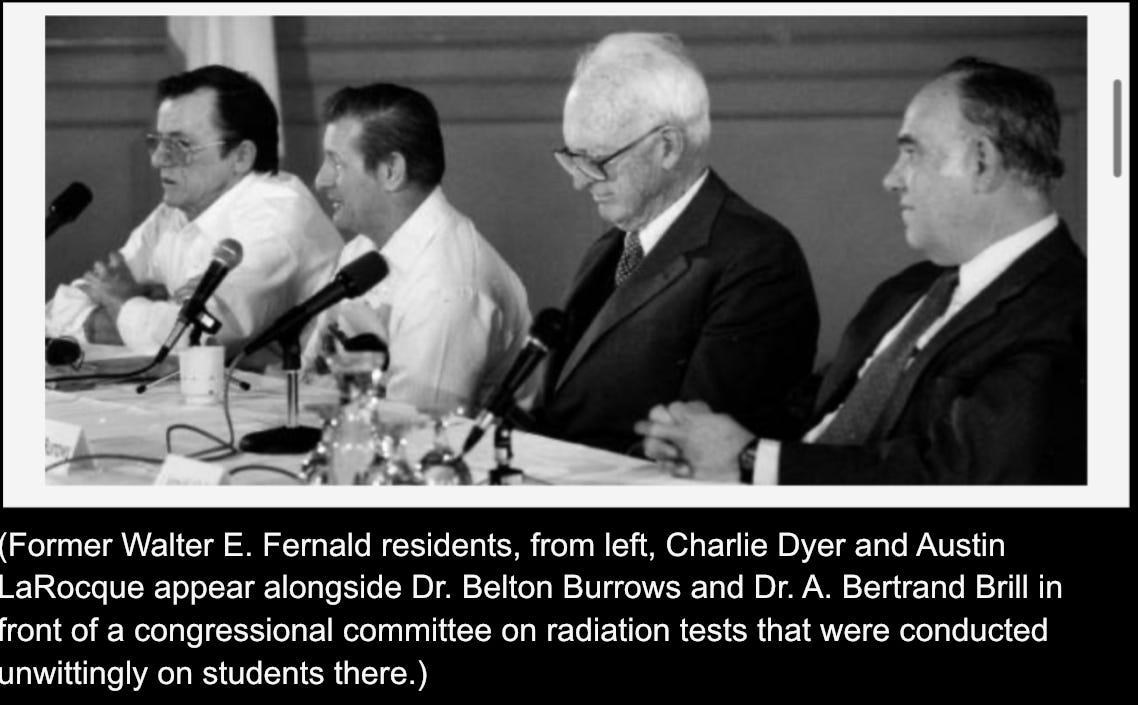

These prisoner experiments remained relatively hidden until the 1970s. In 1976, twenty inmates sued, likening the program to “a little dose of Buchenwald” given stateside. They ultimately settled out of court for modest sums. But the issue wouldn’t die. By the 90s, as the Clinton Administration’s Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments (ACHRE) dug through Cold War secrets, the prisoner studies resurfaced in the spotlight. In one ACHRE public hearing in 1994, ex-prisoners testified about their experiences. Their words could have been lifted from a dystopian novel. One man volunteered thinking “it was a way to serve my country even though I was in prison”, the researchers had pitched it as patriotic duty, and he “bought it”. Others just wanted the petty cash or a break from the monotony of their cells. All of them were betrayed. As ethicist Jonathan Moreno later observed, prisoners were seen as “simply cheap and available” research material in that era – society’s throwaways pressed into service in exchange for a few bucks or privileges. The Nuremberg Code’s insistence on informed consent and absence of coercion was conveniently ignored behind penitentiary walls.

By 1974, in the wake of these scandals (and others like Tuskegee), the U.S. finally imposed stricter rules on human experimentation. The era of using captive and powerless populations for high-risk radiation tests was officially over, at least on paper. In reality, many victims never knew they had been part of an “experiment” until investigative reporters or government inquiries told them decades after the fact. The ultimate insult came in the form of official equivocation. When the ACHRE report was released in 1995, it acknowledged gross violations but often stopped short of outright condemnation of the individuals involved. In the plutonium cases, for example, the University of California’s internal review astonishingly concluded there were no “malevolent” intentions, as if that excused the deeds. Families took great exception to that tepid language. The grandson of Albert Stevens, the CAL-1 patient who unknowingly carried plutonium to his grave, put it plainly: “The people who did this to my grandfather had only to ask themselves how they would feel if they were in his place?”. Any ethical code, he said, “must begin and end with that very simple question.”

And that, perhaps, is the bitter legacy of these experiments. Again and again, the perpetrators, whether military doctors, academic researchers, or corporate-funded scientists, failed to ask the most basic question: What if this were me? What if it were my child being fed radioactive cereal, my father injected with plutonium, my mother blasted with whole-body radiation, or my testicles being irradiated in a prison lab? Instead, they cloaked themselves in cold war urgency and scientific hubris. In secret meeting notes and memos, we see how they justified the unjustifiable. Wright H. Langham, the Los Alamos health physicist overseeing the plutonium excretion studies, wrote bluntly that as a rule, subjects were chosen who were “past forty-five” and “survival for ten years was highly improbable.” They were “hopelessly sick” or “terminal,” he emphasized, suitable for sacrifice. In a chilling 1946 letter to the Rochester team, Langham even encouraged using a larger dose on the next dying patient: if you’re sure someone’s truly terminal, he wrote, why not inject 50 micrograms instead of 5? It would “make my work considerably easier,” he quipped, noting he was “reasonably certain” a bigger dose would do no harm to a patient with one foot in the grave . This is what bureaucratic rationalization looks like: human lives reduced to columns of data, with the only regret being that a low dose makes the analysis harder.

Other officials were equally cavalier. A 1946 Manhattan Project memo by Colonel Friedell described plans at Berkeley where injections would be done “without the knowledge of the patient”; the doctors would simply “assume full responsibility”, since getting a patient release was considered pointless (and in Friedell’s words, a release “was held to be invalid” anyway) . In other words, don’t bother asking, just do it under the usual hospital pretense, and if the patient were to sign anything it’d be meaningless. Such was the modus operandi of an entire generation of medical experiments: Secrecy first, science second, and the human subject dead last. As late as 1967, in a Veterans Administration meeting, officials debated whether to notify living subjects of the plutonium injections now that the experiment was long over. One doctor worried that telling them after all this time “might do more harm than good”, harm to the patient’s psyche, yes, but implicitly also harm to the VA’s reputation. So letters were drafted, scrapped, rewritten in euphemisms. Many subjects went to their graves never learning the truth.

The story of U.S. government radiation experiments is a saga of moral failure at the highest levels, masked by paperwork and patriotism. It’s the sickly mirror image of the Space Race and the fight against communism, a race in which we sacrificed our own citizens’ bodies in the name of “knowledge” and security. The tone of the internal records, when finally brought to light, is often as chilling as the experiments themselves. The people behind these studies were not cackling villains in a comic book; they were buttoned-down physicians, PhDs, and military men who spoke of “experimental parameters,” “tracer doses” and “calibration of human biological systems” while referring to living, breathing individuals as if they were mere test units. They sat in meetings and wrote in journals rationalizing why the ordinary rules of medical ethics didn’t apply, because the nation was in peril, or the subjects were terminal anyway, or the data was just too important.

In the end, President Bill Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the government in 1995, expressing regret to the victims of these radiation experiments. It was a long-overdue gesture, but words alone feel hollow against the backdrop of what actually occurred. The true weight of this history lies in the voices of those who survived and the ghosts of those who didn’t. It lies in the anguished testimony of children grown old, of families who pieced together the truth that their loved ones were betrayed, and of ordinary Americans who learned that their government and trusted institutions viewed them, in a moment of grand national ambition – as disposable.

One father of a plutonium victim, Milton Stadt, told the advisory committee in 1995 how his mother, Janet Stadt (HP-8), went into a Rochester hospital for a scleroderma treatment and a ulcer repair, only to be “pushed over into this lab where these monsters were”. Monsters. It’s a harsh word that no doctor ever wants to hear applied to themselves. But in the cold hindsight of history, when you imagine a frightened boy swallowing oatmeal that “they forgot to mention” was radioactive, or a dying man’s bones being picked apart for plutonium, or a prisoner’s genitals lit up with X-rays as someone times it with a stopwatch, what else can we call those who perpetrated this? Monsters in lab coats, armed with slide rules, grant money, and an ethical blank check signed by the Atomic Energy Commission.

Decades after the fact, we are left with two legacies: scientific data that arguably could have been obtained by other means, and a cautionary tale written in the blood and bones of the powerless. The data lives on in federal guides and scholarly articles, the Langham model of plutonium excretion, the thresholds for acute radiation syndrome, the metabolic pathways of radioisotopes in humans. But the stories of the human subjects must live on too, so that we do not repeat these horrors. The final report of the 1986 Congressional subcommittee said it best: yes, these experiments yielded information, but they are “nonetheless repugnant because human subjects were essentially used as guinea pigs and calibration devices.” The phrase “American Nuclear Guinea Pigs” was the title of that report , and it is an apt epitaph for this dark chapter of our history.

In a just world, the memory of these events serves as a permanent injunction against such abuses. We want to believe “it couldn’t happen again.” Yet, the mindset that enabled these studies, heroic science unmoored from humanity, can creep back whenever fear and secrecy combine. The only vaccine is truth and accountability. That means remembering the names: Elmer Allen, Albert Stevens, Simeon Shaw, Janet Stadt, Fred Boyce, and so many others who unknowingly gave their bodies to science. It means, when confronted with the next moral crossroads, scientists and officials must ask that simple question the experimenters of the Atomic Age failed to: How would I feel if this were done to me or my family?

If the answer is horror, then do not proceed. Because the story you’ve read here is what happens when that question goes unasked, or unanswered.

Fantastic article. Love the subtle invocation of the Golden Rule:

"[S]cientists and officials must ask that simple question the experimenters of the Atomic Age failed to: How would I feel if this were done to me or my family?"

Wow. Horrendous. The only comment I’ll make on this statement :In a just world, the memory of these events serves as a permanent injunction against such abuses. We want to believe “it couldn’t happen again. Yet, the mindset that enabled these studies, heroic science unmoored from humanity, can creep back whenever fear and secrecy combine. The only vaccine is truth and accountability. “

These abuses have and are continuing. The mindset is still present as the last few years have certainly shown. Humans are still viewed as test subjects under the cloak of security and secrecy. There has been no accountability or even admittance of wrong doing. Just “mistakes were made”