This investigation explores the complex relationships between government regulators and the pharmaceutical industry, focusing on the "revolving door" phenomenon wherein individuals move between regulatory agencies and the industries they regulate. By examining historical examples of conflicts of interest, such as the opioid epidemic and the Vioxx scandal, the analysis highlights the potential implications for public health.

Furthermore, it scrutinizes the FDA's budget and the reliance on user fees from private companies, which may compromise the agency's independence. It also presents high-profile cases of the revolving door phenomenon involving individuals such as Scott Gottlieb, Julie Gerberding, and Michael R. Taylor, among others, raising concerns about potential conflicts of interest and regulatory impartiality.

Lastly, I will offer a few policy solutions, including strengthening post-employment restrictions, enhancing transparency, reducing reliance on user fees, and establishing an independent ethics committee, to mitigate conflicts of interest and safeguard public health. By exploring the stories behind these cases, I hope to shed light on an issue that continues to plague our society. Although I endeavored to provide many examples, this only scratches the surface on the significance of this issue. Let’s start with one of the most recent tragic examples.

One Nation Under Scandal

The OxyContin Epidemic and Purdue Pharma

The opioid epidemic in the United States has been linked to the aggressive marketing and promotion of the prescription painkiller OxyContin by its manufacturer, Purdue Pharma. In 2007, the company and three of its top executives pleaded guilty to federal charges of misleading doctors, patients, and regulators about the drug's risks (1). Purdue Pharma has paid out billions of dollars in settlements and penalties since then.

One notable example of conflict of interest involves Dr. Curtis Wright, who was an FDA official responsible for approving OxyContin in 1995. Following the approval, he left the FDA and joined Purdue Pharma as a paid consultant (2). This relationship raised questions about the integrity of the approval process, and whether Wright's decision to approve the drug was influenced by the prospect of future employment with Purdue.

The Vioxx Scandal and Merck

In 2004, the blockbuster painkiller Vioxx was withdrawn from the market after it was discovered that the drug significantly increased the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Manufacturer Merck & Co. faced numerous lawsuits and eventually paid billions in settlements (4).

At the center of the scandal was Dr. David Graham, an FDA safety researcher who publicly criticized the FDA's approval of Vioxx and accused the agency of suppressing evidence of its risks (5). Graham claimed that Merck had exerted undue influence over the FDA's drug review process, resulting in a failure to adequately protect the public.

The Swine Flu Scare and GlaxoSmithKline's Pandemrix

In 2009, a media hyped H1N1 swine flu pandemic swept across the globe, prompting an urgent response from health authorities. One vaccine developed to combat the virus was Pandemrix, produced by pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). European governments, following recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO), swiftly purchased large quantities of the vaccine (6).

However, in the years that followed, it was revealed that Pandemrix had caused narcolepsy, a rare sleep disorder, in hundreds of children and teenagers (7). Questions arose about the relationship between GSK and key WHO officials who had encouraged the use of the vaccine. For example, it was discovered that Dr. Albert Osterhaus, a prominent Dutch virologist and a key influencer in the WHO's pandemic response, held financial ties to GSK (8). These connections cast doubt on the impartiality of the advice provided by health experts and the vaccine's rapid approval.

The EpiPen Price Hike Controversy and Mylan

The EpiPen, a life-saving auto-injector for individuals experiencing severe allergic reactions, came under scrutiny in 2016 when its manufacturer, Mylan, implemented a dramatic price increase (9). The cost of a two-pack of EpiPens skyrocketed from around $100 in 2007 to over $600 in 2016, igniting public outrage and accusations of price gouging.

A crucial figure in this controversy was Senator Joe Manchin, whose daughter Heather Bresch served as Mylan's CEO during the price hike (10). Manchin's position in the government raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest. Some critics argued that the senator's influence may have shielded Mylan from more significant consequences, as he was known to have close ties with the pharmaceutical industry (11). The EpiPen scandal thus highlights the complex web of connections between government officials and pharmaceutical companies, and the potential ramifications for public health and pricing policies.

The Essure Birth Control Scandal and Bayer

Essure, a permanent birth control device manufactured by Bayer, was approved by the FDA in 2002 as a non-surgical alternative to tubal ligation. However, thousands of women reported severe complications from the device, including chronic pain, organ perforation, and unintended pregnancies (12).

A significant factor in this scandal was the cozy relationship between FDA officials and Bayer representatives. For instance, it was revealed that some FDA panel members who reviewed and approved Essure had financial ties to the company, casting doubt on the impartiality of the approval process (13). In 2018, Bayer announced the discontinuation of Essure in the United States (14).

The Sackler Family and the Opioid Crisis

The Sackler family, owners of Purdue Pharma, played a central role in the opioid crisis in the United States. As previously mentioned, Purdue Pharma aggressively marketed OxyContin, which contributed to the widespread addiction to prescription opioids and the subsequent rise in overdose deaths (15).

The Sackler family's connections to government officials and institutions further complicated the issue. For example, the Sacklers donated millions to influential institutions such as the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, earning them significant social and political capital (16). Critics argue that these connections allowed the family to escape the level of scrutiny and accountability they should have faced for their role in the opioid crisis.

In 2021, a bankruptcy court approved a settlement plan for Purdue Pharma, which included billions of dollars in financial penalties and the dissolution of the company (17). However, the Sackler family's ability to evade personal liability for their actions remains a point of contention, highlighting the challenges of untangling conflicts of interest in the pharmaceutical industry.

The Avandia Scandal and GlaxoSmithKline

In 2007, the diabetes drug Avandia, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), came under intense scrutiny when a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine linked it to an increased risk of heart attacks (18). Despite these findings, the FDA allowed the drug to remain on the market, albeit with restrictions and updated warning labels (19).

An investigation by the Senate Finance Committee found that GSK had withheld critical safety data from the FDA and attempted to suppress concerns about Avandia's cardiovascular risks (20). The inquiry also revealed that some FDA officials, responsible for overseeing the drug's safety, had financial ties to GSK (21).

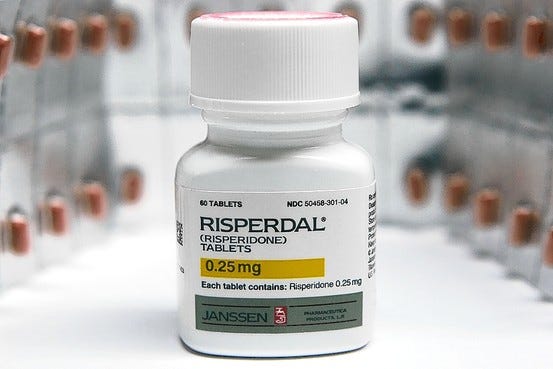

The Risperdal Scandal and Johnson & Johnson

Risperdal, an antipsychotic drug manufactured by Johnson & Johnson (J&J), became the subject of controversy when it was discovered that the company had promoted its off-label use for unapproved conditions, particularly among children and the elderly (22). In 2013, J&J agreed to pay over $2.2 billion in criminal and civil fines to resolve allegations of fraudulent marketing and kickback schemes involving Risperdal (23).

The scandal was further compounded by evidence of cozy relationships between J&J and government officials. For example, the company made substantial campaign contributions to state politicians, who were responsible for overseeing the use of Risperdal in state-funded healthcare programs (24). These financial ties may have influenced regulatory decisions and contributed to the improper promotion of the drug.

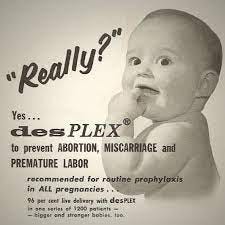

The DES Scandal and Government Regulators

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) was a synthetic estrogen prescribed to pregnant women from the 1940s to the 1970s to prevent miscarriages and premature births. Decades later, it was discovered that DES was linked to a rare form of vaginal cancer in the daughters of women who took the drug, as well as other health issues affecting both the daughters and sons of those women (25).

The DES scandal exposed a significant conflict of interest, as several key government researchers and regulators who had promoted and approved the drug's use held financial interests in companies that produced DES (26). This relationship brought into question the impartiality of the drug's approval and whether the regulators had prioritized the interests of the pharmaceutical industry over public health.

The Zantac Controversy and Sanofi

In 2019, the popular heartburn medication Zantac, produced by Sanofi, was found to contain N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a probable human carcinogen. Subsequent investigations led to a recall of the drug in several countries (27).

The Zantac scandal prompted questions about the relationship between Sanofi and government officials. For example, it was discovered that Sanofi had sponsored trips for FDA officials to attend international conferences (28). These revelations underscored the need for greater transparency and ethical standards in the interactions between pharmaceutical companies and regulators.

The Ghostwriting Scandal and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals

In the early 2000s, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, now a part of Pfizer, faced accusations of using ghostwriters to draft scientific articles that promoted the benefits of its hormone replacement therapy (HRT) drugs Premarin and Prempro (29). These articles, published in prestigious medical journals, were later found to downplay the risks of HRT, such as breast cancer, stroke, and heart disease.

The ghostwriting scandal highlighted the close relationship between pharmaceutical companies and the medical community, including government researchers who were among the listed authors of these articles. The involvement of these researchers raised questions about conflicts of interest and the credibility of scientific research that supports drug approval and marketing (30).

Quid Pro Quo

The FDA's budget consists of two main components: federal appropriations and user fees paid by private companies, primarily from the pharmaceutical and medical device industries. User fees were introduced in 1992 with the passage of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA). The aim was to provide the FDA with additional resources to review and approve new drugs more quickly, without relying solely on taxpayer funding.

As of the fiscal year 2021, the FDA's total budget was around $6.1 billion. Out of this amount, approximately $3.3 billion came from federal budget authority (i.e., taxpayer funding), while about $2.8 billion was derived from user fees (31). This means that approximately 46% of the FDA's budget came from private companies in the form of user fees.

The user fees are collected from various industries regulated by the FDA, including prescription drugs, generic drugs, medical devices, animal drugs, and biosimilar biological products. The fees are charged to companies for services such as reviewing and approving new products, conducting post-market surveillance, and maintaining regulatory compliance. The specific amounts and structures of these fees vary by industry and are negotiated between the FDA and the respective industries, subject to congressional reauthorization every few years.

While user fees have helped the FDA speed up its review and approval processes, they have also raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest. Critics argue that the FDA's reliance on industry funding may compromise its independence and public health mission. To address these concerns, the FDA maintains that user fees are kept separate from its regulatory decision-making process and are primarily used to hire additional staff and support infrastructure improvements. I am not sure how anyone can seriously believe that considering the history of scandals within the FDA and industry. How can citizens be asked to trust the FDA if almost half of its budget is from the very same industries it is mandated to regulate?

To further illustrate the extent of this regulatory capture I’ll provide examples of some recent high-profile individuals who moved between United States regulatory agencies and the industries they regulated.

Wolves In The Henhouse

Scott Gottlieb

Scott Gottlieb served as the Commissioner of the FDA from May 2017 to April 2019. After leaving the FDA, Gottlieb joined Pfizer Inc.'s board of directors in June 2019 (32). He played an influential role in public perception mana during the COVID -19 pandemic, appearing on television almost nightly to recite industry talking points. Not once was his financial ties and role as a Pfizer board member disclose during these appearances. Prior to his tenure at the FDA, Gottlieb had already held various roles in the pharmaceutical industry, including serving on the boards of several companies. Critics argue that his close ties with the industry raise concerns about potential conflicts of interest, as he had a major role in regulating the industry during his time at the FDA.

Julie Gerberding

Julie Gerberding was the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 2002 to 2009. In 2010, she joined Merck & Co., one of the world's largest pharmaceutical companies, as the president of the company's vaccine division (33). While her compensation details are not publicly disclosed, her appointment raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest, as she had previously overseen public health policy and vaccination programs while at the CDC.

Michael R. Taylor

Michael R. Taylor served as the FDA's Deputy Commissioner for Foods and Veterinary Medicine from 2010 to 2016. Before joining the FDA, Taylor had held various positions in the food industry, including working as the Vice President for Public Policy at Monsanto, a leading agricultural biotechnology company (34). After leaving the FDA, Taylor joined the board of directors of Clear Labs, a food safety testing company, in 2017 (35). The revolving door between Taylor's positions in the regulatory agency and the industry has raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest.

Thomas Südhof

Thomas Südhof, a Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist, was appointed to the FDA's Science Board in 2017. In 2018, Südhof joined the scientific advisory board of BlackThorn Therapeutics, a biopharmaceutical company focused on developing treatments for neurobehavioral disorders (36). Südhof's dual roles raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest, as his position on the FDA's Science Board put him in a position to influence the agency's decision-making processes.

Robert Califf

Robert Califf served as the Commissioner of the FDA from February 2016 to January 2017. Before joining the FDA, Califf had extensive ties to the pharmaceutical industry, including serving as a paid consultant for companies such as Merck, Novartis, and Eli Lilly. He received millions of dollars in consulting fees and research funding from pharmaceutical companies. After leaving the FDA, Califf joined Alphabet's health division, Verily Life Sciences, and the Duke Clinical Research Institute (37). Critics argue that his close ties with the industry raise concerns about potential conflicts of interest during his tenure at the FDA.

Darrell Abernethy

Darrell Abernethy worked at the FDA from 2004 to 2018, serving in various roles, including Associate Director for Drug Safety in the Office of Clinical Pharmacology. In 2018, Abernethy joined the biopharmaceutical company Otsuka as the Chief Science Officer of Otsuka's Global Clinical Development (38). Abernethy's move from the FDA to a private pharmaceutical company raises concerns about potential conflicts of interest, as he had a significant role in overseeing drug safety during his time at the FDA.

These examples further demonstrate the "revolving door" phenomenon, where individuals move between regulatory agencies and the industries they regulate. This pattern has raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest and the need for more stringent policies to minimize the potential for undue influence in regulatory decision-making.

Closing The Revolving Doors

There are many policy adjustments that could help hinder the ability of government officials profiting from their time regulating the industry, really it’s just a matter of will. As you have learned, the will or appetite to do so is extremely limited. Sure lip service is paid momentarily when a scandal is reported in the press but it almost immediately fades into the abyss that is the 24/7 news cycle. It is easy to overlook these entanglements but they have real life consequences. Many people have been injured or worse by these decisions, or lack thereof, with virtually zero culpability other than some fines or sanctions. Nonetheless I thought it prudent to present some practical solutions that can begin to chip away at the behemoth that is the regulatory capture environment we finds ourselves in presently.

Strengthening Disclosure Requirements

To increase transparency and reduce conflicts of interest, policymakers should enforce stricter disclosure requirements for both government officials and pharmaceutical companies. This includes requiring all financial ties and relationships to be disclosed in regulatory processes, research publications, and policy decisions. By mandating comprehensive disclosure, stakeholders will be better equipped to identify and address potential conflicts of interest, fostering greater trust in the regulatory process and scientific research.

Banning Gifts and Sponsorships

Prohibiting pharmaceutical companies from providing gifts, sponsorships, or other financial incentives to government officials and healthcare providers can help minimize conflicts of interest. This policy would prevent companies from using financial leverage to influence regulatory decisions and prescribing practices, ensuring that medical professionals make decisions based solely on the best interests of patients and public health.

Implementing Revolving Door Restrictions

Policymakers should enforce stricter "revolving door" restrictions that regulate the movement of individuals between the government and the pharmaceutical industry. These restrictions could include mandatory waiting periods before former government officials can work for pharmaceutical companies or vice versa. By reducing the frequency of individuals switching between the two sectors, this policy aims to minimize the potential for conflicts of interest and undue influence.

Expanding Independent Funding for Research

Increasing independent funding for medical research can reduce the reliance on pharmaceutical industry funding, which often comes with strings attached. By supporting research initiatives with public funding, the government can help ensure that research remains objective, unbiased, and focused on public health priorities, rather than the financial interests of pharmaceutical companies.

Enhancing Regulatory Oversight and Enforcement

Strengthening oversight and enforcement mechanisms can help ensure compliance with existing regulations and hold both government officials and pharmaceutical companies accountable for their actions. This could involve providing regulatory agencies with additional resources, such as increased funding and staff, as well as implementing more stringent penalties for noncompliance. Enhanced oversight and enforcement can deter conflicts of interest and promote a culture of transparency and ethical conduct in the pharmaceutical industry.

Promoting Collaborative Decision-Making

Encouraging a collaborative approach to decision-making can help to ensure that a broad range of perspectives and expertise are represented in regulatory processes. This could involve the establishment of multidisciplinary advisory committees composed of experts from various fields, including medicine, public health, ethics, and patient advocacy. By promoting collaboration, policymakers can reduce the potential for undue influence and create a more balanced and robust decision-making process.

These policy solutions provide a roadmap for addressing conflicts of interest between government officials and pharmaceutical companies. By promoting transparency, accountability, and collaboration, these measures can help to safeguard public health and restore trust in the regulatory process and healthcare system.

In a world where public health remains a cornerstone of societal well-being, the revolving door phenomenon between government regulators and the pharmaceutical industry casts a troubling shadow over the integrity of the very institutions entrusted to safeguard our health. As officials cycle between these sectors, the line separating regulator and industry advocate becomes increasingly blurred, raising the specter of a compromised system that prioritizes profit over people.

The far-reaching implications of this phenomenon are evident in the tragic tales of the opioid epidemic and the Vioxx scandal, which serve as chilling reminders of how the interwoven relationships between regulators and pharmaceutical giants can place innocent lives at risk. As regulators succumb to the lure of lucrative positions within the industry, the public's trust in the objectivity and impartiality of the agencies that oversee drug approval and safety begins to erode.

The revolving door phenomenon also threatens to undermine scientific rigor and the critical evaluation of drug safety and efficacy, as cozy relationships between industry and regulators fosters an environment where potential risks are downplayed or even overlooked. In such a climate, new drugs might be rushed through the approval process, leaving the public exposed to unforeseen consequences and long-term health effects. This has been on full display during the COVID-19 pandemic where every code of medical ethics were shattered into pieces. In favor of top down authoritarianism with no credible scientific evidence to justify the public health measures put into place.

Moreover, the reliance on user fees from the pharmaceutical and medical device industries to fund regulatory agencies like the FDA has created a dangerous dependency that may incentivize regulators to prioritize the interests of their financiers above the well-being of the public. This financial entanglement raises concerns about the impartiality of regulatory decisions, leading to the inescapable conclusion that public health is being sacrificed on the altar of profit.

In a time when society faces an array of unprecedented public health challenges, from pandemics to the explosive growth of chronic diseases, the revolving door phenomenon exposes a critical vulnerability at the heart of our healthcare system. As we continue to grapple with the consequences of this tangled web of interests, we must remain vigilant in our quest for transparency and accountability.

Sources:

(1)https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/10/business/11drug-web.html

(2) https://www.propublica.org/article/the-former-fda-advisor-who-approved-a-drug-for-massive-sales-and-then-joined

(3) https://www.propublica.org/article/fda-nominee-califf-got-millions-industry

(4)https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/09/business/09merck.html

(5)https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4175679

(6) https://www.reuters.com/article/us-flu-pandemrix/pandemrix-swine-flu-shot-posed-no-extra-narcolepsy-risk-in-adults-study-idUSBRE89N0T220121024

(7) https://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f3037

(8)https://www.dutchnews.nl/news/2009/11/top_virologist_also_has_big_ph/

(9)https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/22/business/epipen-mylan-fda-congress.html

(10) https://www.businessinsider.com/epipen-controversy-mylan-ceo-heather-bresch-joe-manchin-2016-8

(11) https://www.opensecrets.org/members-of-congress/summary?cid=N00032838

(12)https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/20/health/bayer-essure-birth-control.html

(13)https://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/healthwellness/2015/09/20/essure/qp1dVzt8WdBjJrXaDMJ0UK/story.html

(14) https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/07/20/630798067/bayer-will-stop-selling-essure-birth-control-implants

(15)https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/29/health/purdue-opioids-oxycontin.html

(16)https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/30/the-family-that-built-an-empire-of-pain

(17) https://apnews.com/article/business-health-opioids-purdue-pharma-opioid-crisis-2b3e4457113d8d394db9c489f861a15a

(18)https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa072761

(19)https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/24/health/policy/24avandia.html

(20)https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/REPORT%20-%20Staff%20Report%20on%20GSK.pdf

(21) https://www.propublica.org/article/conflicts-of-interest-marred-fdas-avandia-review

(22)https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/17/business/johnson-johnson-is-ordered-to-pay-1-75-million-in-risperdal-case.html

(23) https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/johnson-johnson-pay-more-22-billion-resolve-criminal-and-civil-investigations

(24)https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/09/johnson-johnson-risperdal-political-contributions

(25) https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/hormones/des-fact-sheet

(26)https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1739949/

(27)https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/13/health/zantac-recall-ndma.html

(28) https://www.propublica.org/article/fda-and-drug-companies-share-cozy-relationship

(29)https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/05/health/research/05ghost.html

(30)https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/184624

(31) https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-basics/fact-sheet-fda-glance

(32)https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/27/health/scott-gottlieb-pfizer.html

(33) https://www.reuters.com/article/us-merck-idUSTRE5BK2K520091221

(34) https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/17/AR2009071703609.html

(35)https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170926005445/en/Michael-Taylor-Former-FDA-Deputy-Commissioner-for-Foods-and-Veterinary-Medicine-Joins-Clear-Labs-Board

(36) https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/may-16-2017-meeting-fdas-science-board

(37) https://www.statnews.com/2017/03/15/robert-califf-fda-alphabet/

(38) https://www.linkedin.com/in/darrell-abernethy-851a0126/